From miswired brain to psychopathology – modelling neurodevelopmental disorders in mice

It takes a lot of genes to wire the human brain. Billions of cells, of a myriad different types have to be specified, directed to migrate to the right position, organised in clusters or layers, and finally connected to their appropriate targets. When the genes that specify these neurodevelopmental processes are mutated, the result can be severe impairment in function, which can manifest as neurological or psychiatric disease.

How those kinds of neurodevelopmental defects actually lead to the emergence of particular pathological states – like psychosis or seizures or social withdrawal – is a mystery, however. Many researchers are trying to tackle this problem using mouse models – animals carrying mutations known to cause autism or schizophrenia in humans, for example. A recent study from my own lab (open access in PLoS One) adds to this effort by examining the consequences of mutation of an important neurodevelopmental gene and providing evidence that the mice end up in a state resembling psychosis. In this case, we start with a discovery in mice as an entry point to the underlying neurodevelopmental processes.

In just the past few years, over a hundred different mutations have been discovered that are believed to cause disorders like autism or schizophrenia. In many cases, particular mutations can actually predispose to many different disorders, having been linked in different patients to ADHD, epilepsy, mental retardation or intellectual disability, Tourette’s syndrome, depression, bipolar disorder and others. These clinical categories may thus represent more or less distinct endpoints that can arise from common neurodevelopmental origins.

For a condition like schizophrenia, the genetic overlap with other conditions does not invalidate the clinical category. There is still something distinctive about the symptoms of this disorder that needs to be explained. I have argued that schizophrenia can clearly be caused by single mutations in any of a very large number of different genes, many with roles in neurodevelopment. If that model is correct, then the big question is: how do these presumably diverse neurodevelopmental insults ultimately converge on that specific phenotype? It is, after all, a highly unusual condition. The positive symptoms of psychosis – hallucinations and delusions, for example – especially require an explanation. If we view the brain from an engineering perspective, then we can say that the system is not just not working well – it is failing in a particular and peculiar manner.

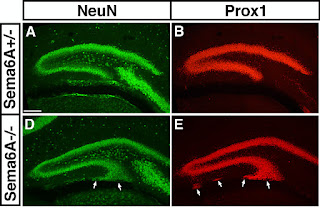

To try to address how this kind of state can arise we have been investigating a particular mouse – one with a mutation in a gene called Semaphorin-6A. This gene encodes a protein that spans the membranes of nerve cells, acting in some contexts as a signal to other cells and in other contexts as a receptor of information. It has been implicated in controlling cell migration, the guidance of growing axons, the specification of synaptic connectivity and other processes. It is deployed in many parts of the developing brain and required for proper development in the cerebral cortex, hippocampus, thalamus, cerebellum, retina, spinal cord, and probably other areas we don’t yet know about.

Despite widespread cellular disorganisation and miswiring in their brains, Sema6A mutant mice seem overtly pretty normal. They are quite healthy and fertile and a casual inspection would not pick them out as different from their littermates. However, more detailed investigation revealed electrophysiological and behavioural differences that piqued our interest.

Because these animals have a subtly malformed hippocampus, which looks superficially like the kind of neuropathology observed in many cases of temporal lobe epilepsy, we wanted to test if they had seizures. To do this we attached electrodes to their scalp and recorded their electroencephalogram (or EEG). This technique measures patterned electrical activity in the underlying parts of the brain and showed quite clearly that these animals do not have seizures. But it did show something else – a generally elevated amount of activity in these animals all the time.

Because these animals have a subtly malformed hippocampus, which looks superficially like the kind of neuropathology observed in many cases of temporal lobe epilepsy, we wanted to test if they had seizures. To do this we attached electrodes to their scalp and recorded their electroencephalogram (or EEG). This technique measures patterned electrical activity in the underlying parts of the brain and showed quite clearly that these animals do not have seizures. But it did show something else – a generally elevated amount of activity in these animals all the time.

What was particularly interesting about this is that the pattern of change (a specific increase in alpha frequency oscillations) was very similar to that reported in animals that are sensitised to amphetamine – a well-used model of psychosis in rodents. High doses of amphetamine can acutely induce psychosis in humans and a suite of behavioural responses in rodents. In addition, a regimen of repeated low doses of amphetamine over an extended time period can induce sensitisation to the effects of this drug in rodents, characterised by behavioural differences, like hyperlocomotion, as well as the EEG differences mentioned above. Amphetamine is believed to cause these effects by inducing increases in dopaminergic signaling, either chronically, or to acute stimuli.

This was of particular interest to us, as that kind of hyperdopaminergic state is thought to be a final common pathway underlying psychosis in humans. Alterations in dopamine signaling are observed in schizophrenia patients (using PET imaging) and also in all relevant animal models so far studied.

To explore possible further parallels to these effects in Sema6A mutants we examined their behaviour and found a very similar profile to many known animal models of psychosis, namely hyperlocomotion and a hyper-exploratory phenotype (in addition to various other phenotypes, like a defect in working memory). The positive symptoms of psychosis can be ameliorated in humans with a number of different antipsychotic drugs, which have in common a blocking action on dopamine receptors. Administering such drugs to the Sema6A mutants normalised both their activity levels and the EEG (at a dose that had no effect on wild-type animals).

These data are at least consistent with (though they by no means prove) the hypothesis that Sema6A mutants end up in a hyperdopaminergic state. But how do they end up in that state? There does not seem to be a direct effect on the development of the dopaminergic system – Sema6A is at least not required to direct these axons to their normal targets.

Our working hypothesis is that the changes to the dopaminergic system emerge over time, as a secondary response to the primary neurodevelopmental defects seen in these animals.  It is well documented that early alterations, for example to the hippocampus, can have cascading effects over subsequent activity-dependent development and maturation of brain circuits. In particular, it can alter the excitatory drive to the part of the midbrain where dopamine neurons are located, in turn altering dopaminergic tone in the forebrain. This can induce compensatory changes that ultimately, in this context, may prove maladaptive, pushing the system into a pathological state, which may be self-reinforcing.

It is well documented that early alterations, for example to the hippocampus, can have cascading effects over subsequent activity-dependent development and maturation of brain circuits. In particular, it can alter the excitatory drive to the part of the midbrain where dopamine neurons are located, in turn altering dopaminergic tone in the forebrain. This can induce compensatory changes that ultimately, in this context, may prove maladaptive, pushing the system into a pathological state, which may be self-reinforcing.

For now, this is just a hypothesis and one that we (and many other researchers working on other models) are working to test. The important thing is that it provides a possible explanation for why so many different mutations can result in this strange phenotype, which manifests in humans as psychosis. If this emerges as a secondary response to a range of primary insults then that reactive process provides a common pathway of convergence on a final phenotype. Importantly, it also provides a possible point of early intervention – it may not be possible to “correct” early differences in brain wiring but it may be possible to prevent them causing transition to a state of florid psychopathology.

Rünker AE, O'Tuathaigh C, Dunleavy M, Morris DW, Little GE, Corvin AP, Gill M, Henshall DC, Waddington JL, & Mitchell KJ (2011). Mutation of Semaphorin-6A disrupts limbic and cortical connectivity and models neurodevelopmental psychopathology. PloS one, 6 (11) PMID: 22132072

Mitchell, K., Huang, Z., Moghaddam, B., & Sawa, A. (2011). Following the genes: a framework for animal modeling of psychiatric disorders BMC Biology, 9 (1) DOI: 10.1186/1741-7007-9-76

Mitchell, K. (2011). The genetics of neurodevelopmental disease Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 21 (1), 197-203 DOI: 10.1016/j.conb.2010.08.009

Howes, O., & Kapur, S. (2009). The Dopamine Hypothesis of Schizophrenia: Version III--The Final Common Pathway Schizophrenia Bulletin, 35 (3), 549-562 DOI: 10.1093/schbul/sbp006

It is such an interesting thing having this post of yours. I was interested with the topic as well as the flow of the story. Keep up doing this.party pills

ReplyDeleteSuch a useful information, I will be checking your blog for further updates and information.

ReplyDeletebusiness dissertation templates

There is definitely so much that goes into the genes in your brain. So much more research that needs to be done here on genes. So much involved with how the genes work. http://printingservices4businesses.tumblr.com/

ReplyDeleteI think more updates and will be returning. I have filtered for qualified edifying substance of this calibre all through the past various hours. www.cafe-vn.co.uk |

ReplyDeletewww.shoers.co.uk |

www.abortionstatistics.co.uk |

www.kellyllorennacd.co.uk |

www.matthewsawyer.co.uk |

www.chris-burke.co.uk |

www.restaurant123.co.uk |

www.londonspeaker.co.uk |

www.rioscoffee.co.uk |

www.bikesandboards.co.uk |