Nerves of a feather, wire together

Finding your soulmate, for a neuron, is a daunting task. With so many opportunities for casual hook-ups, how do you know when you find “the one”?

In the early 1960’s Roger Sperry proposed his famous “chemoaffinity theory” to explain how neural connectivity arises. This was based on observations of remarkable specificity in the projections of nerves regenerating from the eye of frogs to their targets in the brain. His first version of this theory proposed that each neuron found its target by expression of matching labels on their respective surfaces. He quickly realised, however, that with ~200,000 neurons in the retina, the genome was not large enough to encode separate connectivity molecules for each one. This led him to the insight that a regular array of connections of one field of neurons (like the retina) across a target field (the optic tectum in this case) could be readily achieved by gradients of only one or a few molecules.

In the early 1960’s Roger Sperry proposed his famous “chemoaffinity theory” to explain how neural connectivity arises. This was based on observations of remarkable specificity in the projections of nerves regenerating from the eye of frogs to their targets in the brain. His first version of this theory proposed that each neuron found its target by expression of matching labels on their respective surfaces. He quickly realised, however, that with ~200,000 neurons in the retina, the genome was not large enough to encode separate connectivity molecules for each one. This led him to the insight that a regular array of connections of one field of neurons (like the retina) across a target field (the optic tectum in this case) could be readily achieved by gradients of only one or a few molecules.

The molecules in question, Ephrins and Eph receptors, were discovered thirty-some years later. They are now known to control topographic projections of sets of neurons to other sets of neurons across many areas of the brain, such that nearest-neighbour relationships are maintained (e.g., neurons next to each other in the retina connect to neurons next to each other in the tectum). In this way, the map of the visual world that is generated in the retina is transmitted intact to its targets. Actually, maintenance of nearest-neighbour topography seems to be a general property of projections between any two areas, even ones that do not obviously map some external property across them.

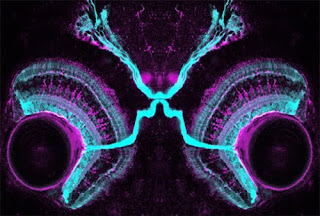

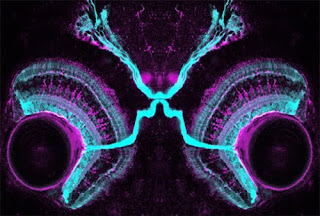

But the idea of matching labels was not wrong – they do exist and they play a very important part in an earlier step of wiring – finding the correct target region in the first place. This is nicely illustrated by a beautiful paper studying projections of retinal neurons in the mouse, which implicates proteins in the Cadherin family in this process.

In the retina, photoreceptor cells sense light and transmit this information, through a couple of relays, to retinal ganglion cells (RGCs). These are the cells that send their projections out of the retina, through the optic nerve, to the brain. But the tectum is not the only target of these neurons. There are, in fact, at least 20 different types of RGCs with distinct functions that project from the retina to various parts of the brain.

In the retina, photoreceptor cells sense light and transmit this information, through a couple of relays, to retinal ganglion cells (RGCs). These are the cells that send their projections out of the retina, through the optic nerve, to the brain. But the tectum is not the only target of these neurons. There are, in fact, at least 20 different types of RGCs with distinct functions that project from the retina to various parts of the brain.

In mammals, “seeing” is mediated by projections to the visual centre of the thalamus, which projects in turn to the primary visual cortex. But conscious vision is only one thing we use our eyes for. The equivalent of the tectum, called the superior colliculus in mammals, is also a target for RGCs, and mediates reflexive eye movements, head turns and shifts of attention. (It might even be responsible for blindsight – subconscious visual responsiveness in consciously blind patients). Other RGCs send messages to regions controlling circadian rhythms (the suprachiasmatic nuclei) or pupillary reflexes (areas of the midbrain called the olivary pretectal nuclei).

In mammals, “seeing” is mediated by projections to the visual centre of the thalamus, which projects in turn to the primary visual cortex. But conscious vision is only one thing we use our eyes for. The equivalent of the tectum, called the superior colliculus in mammals, is also a target for RGCs, and mediates reflexive eye movements, head turns and shifts of attention. (It might even be responsible for blindsight – subconscious visual responsiveness in consciously blind patients). Other RGCs send messages to regions controlling circadian rhythms (the suprachiasmatic nuclei) or pupillary reflexes (areas of the midbrain called the olivary pretectal nuclei).

These RGCs express a photoresponsive pigment (melanopsin) and respond to light directly. This likely reflects the fact that early eyes contained both ciliated photoreceptors (like current rods and cones) and rhabdomeric photoreceptors (possibly the ancestors of RGCs and other retinal cells).

So how do these various RGCs know which part of the brain to project to? This was the question investigated by Andrew Huberman and colleagues, who looked for inspiration to the fly eye. It had previously been shown that a member of the Cadherin family of proteins was involved in fly photoreceptor axons choosing the right layer to project to in the optic lobe. Cadherins are “homophilic” adhesion molecules – they are expressed on the surface of cells and like to bind to themselves. Two cells expressing the same Cadherin protein will therefore stick to each other. This stickiness may be used as a signal to make a synaptic connection between a neuron and its target.

Cadherins are “homophilic” adhesion molecules – they are expressed on the surface of cells and like to bind to themselves. Two cells expressing the same Cadherin protein will therefore stick to each other. This stickiness may be used as a signal to make a synaptic connection between a neuron and its target.

The protein implicated in flies, N-Cadherin, is widely expressed in mammals and thus unlikely to specify connections to different targets of the retina. But Cadherins comprise a large family of proteins, suggesting that other members might play more specific roles. This turns out to be the case – a screen of these proteins revealed several expressed in distinct regions of the brain receiving inputs from subtypes of RGCs. One in particular, Cadherin-6, is expressed in non-image-forming brain regions that receive retinal inputs – those controlling eye movements and pupillary reflexes, for example. The protein is also expressed in a very discrete subset of RGCs – specifically those that project to the Cadherin-6-expressing targets in the brain.

The obvious hypothesis was that this matching protein expression allowed those RGCs to recognise their correct targets by literally sticking to them. To test this, they analysed these projections in mice lacking the Cadherin-6 molecule. Sure enough, the projections to those targets were severely affected – the axons spread out over the general area of the brain but failed to zero in on the specific subregions that they normally targeted.

These results illustrate a general principle likely to be repeated using different Cadherins in different RGC subsets and also in other parts of the brain. Indeed, a paper published at the same time shows that Cadherin-9 may play a similar function in the developing hippocampus. In addition, other families of molecules, such as Leucine-Rich Repeat proteins may play a similar role as synaptic matchmakers by promoting homophilic adhesion between neurons and their targets. (Both Cadherins and LRR proteins also have important “heterophilic” interactions with other proteins).

The expansion of these families in vertebrates could conceivably be linked to the greater complexity of the nervous system, which presumably requires more such labels to specify it. But these molecules may be of more than just academic interest in understanding the molecular logic and evolution of the genetic program that specifies brain wiring. Mutations in various members of the Cadherin (and related protocadherin) and LRR gene families have also been implicated in neurodevelopmental disorders, including autism, schizophrenia, Tourette’s syndrome and others. Defining the molecules and mechanisms involved in normal development may thus be crucial to understanding the roots of neurodevelopmental disease.

Osterhout, J., Josten, N., Yamada, J., Pan, F., Wu, S., Nguyen, P., Panagiotakos, G., Inoue, Y., Egusa, S., Volgyi, B., Inoue, T., Bloomfield, S., Barres, B., Berson, D., Feldheim, D., & Huberman, A. (2011). Cadherin-6 Mediates Axon-Target Matching in a Non-Image-Forming Visual Circuit Neuron, 71 (4), 632-639 DOI: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.07.006

Williams, M., Wilke, S., Daggett, A., Davis, E., Otto, S., Ravi, D., Ripley, B., Bushong, E., Ellisman, M., Klein, G., & Ghosh, A. (2011). Cadherin-9 Regulates Synapse-Specific Differentiation in the Developing Hippocampus Neuron, 71 (4), 640-655 DOI: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.06.019

In the early 1960’s Roger Sperry proposed his famous “chemoaffinity theory” to explain how neural connectivity arises. This was based on observations of remarkable specificity in the projections of nerves regenerating from the eye of frogs to their targets in the brain. His first version of this theory proposed that each neuron found its target by expression of matching labels on their respective surfaces. He quickly realised, however, that with ~200,000 neurons in the retina, the genome was not large enough to encode separate connectivity molecules for each one. This led him to the insight that a regular array of connections of one field of neurons (like the retina) across a target field (the optic tectum in this case) could be readily achieved by gradients of only one or a few molecules.

In the early 1960’s Roger Sperry proposed his famous “chemoaffinity theory” to explain how neural connectivity arises. This was based on observations of remarkable specificity in the projections of nerves regenerating from the eye of frogs to their targets in the brain. His first version of this theory proposed that each neuron found its target by expression of matching labels on their respective surfaces. He quickly realised, however, that with ~200,000 neurons in the retina, the genome was not large enough to encode separate connectivity molecules for each one. This led him to the insight that a regular array of connections of one field of neurons (like the retina) across a target field (the optic tectum in this case) could be readily achieved by gradients of only one or a few molecules. The molecules in question, Ephrins and Eph receptors, were discovered thirty-some years later. They are now known to control topographic projections of sets of neurons to other sets of neurons across many areas of the brain, such that nearest-neighbour relationships are maintained (e.g., neurons next to each other in the retina connect to neurons next to each other in the tectum). In this way, the map of the visual world that is generated in the retina is transmitted intact to its targets. Actually, maintenance of nearest-neighbour topography seems to be a general property of projections between any two areas, even ones that do not obviously map some external property across them.

But the idea of matching labels was not wrong – they do exist and they play a very important part in an earlier step of wiring – finding the correct target region in the first place. This is nicely illustrated by a beautiful paper studying projections of retinal neurons in the mouse, which implicates proteins in the Cadherin family in this process.

In the retina, photoreceptor cells sense light and transmit this information, through a couple of relays, to retinal ganglion cells (RGCs). These are the cells that send their projections out of the retina, through the optic nerve, to the brain. But the tectum is not the only target of these neurons. There are, in fact, at least 20 different types of RGCs with distinct functions that project from the retina to various parts of the brain.

In the retina, photoreceptor cells sense light and transmit this information, through a couple of relays, to retinal ganglion cells (RGCs). These are the cells that send their projections out of the retina, through the optic nerve, to the brain. But the tectum is not the only target of these neurons. There are, in fact, at least 20 different types of RGCs with distinct functions that project from the retina to various parts of the brain.  In mammals, “seeing” is mediated by projections to the visual centre of the thalamus, which projects in turn to the primary visual cortex. But conscious vision is only one thing we use our eyes for. The equivalent of the tectum, called the superior colliculus in mammals, is also a target for RGCs, and mediates reflexive eye movements, head turns and shifts of attention. (It might even be responsible for blindsight – subconscious visual responsiveness in consciously blind patients). Other RGCs send messages to regions controlling circadian rhythms (the suprachiasmatic nuclei) or pupillary reflexes (areas of the midbrain called the olivary pretectal nuclei).

In mammals, “seeing” is mediated by projections to the visual centre of the thalamus, which projects in turn to the primary visual cortex. But conscious vision is only one thing we use our eyes for. The equivalent of the tectum, called the superior colliculus in mammals, is also a target for RGCs, and mediates reflexive eye movements, head turns and shifts of attention. (It might even be responsible for blindsight – subconscious visual responsiveness in consciously blind patients). Other RGCs send messages to regions controlling circadian rhythms (the suprachiasmatic nuclei) or pupillary reflexes (areas of the midbrain called the olivary pretectal nuclei).These RGCs express a photoresponsive pigment (melanopsin) and respond to light directly. This likely reflects the fact that early eyes contained both ciliated photoreceptors (like current rods and cones) and rhabdomeric photoreceptors (possibly the ancestors of RGCs and other retinal cells).

So how do these various RGCs know which part of the brain to project to? This was the question investigated by Andrew Huberman and colleagues, who looked for inspiration to the fly eye. It had previously been shown that a member of the Cadherin family of proteins was involved in fly photoreceptor axons choosing the right layer to project to in the optic lobe.

Cadherins are “homophilic” adhesion molecules – they are expressed on the surface of cells and like to bind to themselves. Two cells expressing the same Cadherin protein will therefore stick to each other. This stickiness may be used as a signal to make a synaptic connection between a neuron and its target.

Cadherins are “homophilic” adhesion molecules – they are expressed on the surface of cells and like to bind to themselves. Two cells expressing the same Cadherin protein will therefore stick to each other. This stickiness may be used as a signal to make a synaptic connection between a neuron and its target. The protein implicated in flies, N-Cadherin, is widely expressed in mammals and thus unlikely to specify connections to different targets of the retina. But Cadherins comprise a large family of proteins, suggesting that other members might play more specific roles. This turns out to be the case – a screen of these proteins revealed several expressed in distinct regions of the brain receiving inputs from subtypes of RGCs. One in particular, Cadherin-6, is expressed in non-image-forming brain regions that receive retinal inputs – those controlling eye movements and pupillary reflexes, for example. The protein is also expressed in a very discrete subset of RGCs – specifically those that project to the Cadherin-6-expressing targets in the brain.

The obvious hypothesis was that this matching protein expression allowed those RGCs to recognise their correct targets by literally sticking to them. To test this, they analysed these projections in mice lacking the Cadherin-6 molecule. Sure enough, the projections to those targets were severely affected – the axons spread out over the general area of the brain but failed to zero in on the specific subregions that they normally targeted.

These results illustrate a general principle likely to be repeated using different Cadherins in different RGC subsets and also in other parts of the brain. Indeed, a paper published at the same time shows that Cadherin-9 may play a similar function in the developing hippocampus. In addition, other families of molecules, such as Leucine-Rich Repeat proteins may play a similar role as synaptic matchmakers by promoting homophilic adhesion between neurons and their targets. (Both Cadherins and LRR proteins also have important “heterophilic” interactions with other proteins).

The expansion of these families in vertebrates could conceivably be linked to the greater complexity of the nervous system, which presumably requires more such labels to specify it. But these molecules may be of more than just academic interest in understanding the molecular logic and evolution of the genetic program that specifies brain wiring. Mutations in various members of the Cadherin (and related protocadherin) and LRR gene families have also been implicated in neurodevelopmental disorders, including autism, schizophrenia, Tourette’s syndrome and others. Defining the molecules and mechanisms involved in normal development may thus be crucial to understanding the roots of neurodevelopmental disease.

Osterhout, J., Josten, N., Yamada, J., Pan, F., Wu, S., Nguyen, P., Panagiotakos, G., Inoue, Y., Egusa, S., Volgyi, B., Inoue, T., Bloomfield, S., Barres, B., Berson, D., Feldheim, D., & Huberman, A. (2011). Cadherin-6 Mediates Axon-Target Matching in a Non-Image-Forming Visual Circuit Neuron, 71 (4), 632-639 DOI: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.07.006

Williams, M., Wilke, S., Daggett, A., Davis, E., Otto, S., Ravi, D., Ripley, B., Bushong, E., Ellisman, M., Klein, G., & Ghosh, A. (2011). Cadherin-9 Regulates Synapse-Specific Differentiation in the Developing Hippocampus Neuron, 71 (4), 640-655 DOI: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.06.019

Somewhat OT but here goes. How exactly does neuroplasticity work? We know from scans that heavily used areas of the brain expand to the surrounding areas. How does a neuron signal to its neighbor that it needs help? And why would a neuron drop what it currently knows to take on new functionality? This should be fairly easy to figure out, you can use nanowires to listen in on single neurons or lay a grid across the cortex to listen in.

ReplyDeleteI see two possibilities, do you believe in good or evil neurons?

1. One neuron calls for help to neighboring neurons and they altruistically go to help.

2. One neuron sends out signals that wipe functionality from neighboring neurons and instructs them to copy the sending message.

Would be Nobel prize to find out.

Dean

Thank you for your wonderful and precious post.Here,I take down more points to my study.Thank you,Thank you lot for your post.And i want regular updation of your site.

ReplyDeleteAsian Recipes

The nourishment is in the form of vitamins and minerals.Natural products are the only possible way via which you can increase the production of this protein in the body.

ReplyDeletedermatologist vancouver

The concepts are good, but I think sentences are a little long, and sometimes hard to understand. Using simpler and more usual words helps to

ReplyDeleteGet More Instagram Followers

This is definitely so amazing to see how the brain works this way. So much to get from it all here. The mind definitely works in mysterious ways. So much to learn from it. Home Plumbing Journal

ReplyDeleteYour post contain upon the comprehensive and vast structure of brain tissues and you described very well the working of these tissues in the brain. I learn so much from your brain. Thank you so much for such impressive post. traumatic brain injury

ReplyDeleteI am new to this blog, so i dont have any idea to share my thoughts about this post, can you hlep me.?

ReplyDeleteSalon Chino Hills