Top-down causation and the emergence of agency

There is a paradox at the heart of modern

neuroscience. As we succeed in explaining more and more cognitive operations in

terms of patterns of electrical activity of specific neural circuits, it seems

we move ever farther from bridging the gap between the physical and the mental.

Indeed, each advance seems to further relegate mental activity to the status of

epiphenomenon – something that emerges from the physical activity of the brain

but that plays no part in controlling it. It seems difficult to reconcile the

reductionist, reverse-engineering approach to brain function with the idea that

we human beings have thoughts, desires, goals and beliefs that influence our

actions. If actions are driven by the physical flow of ions through networks of

neurons, then is there any room or even any need for psychological explanations

of behaviour?

There is a paradox at the heart of modern

neuroscience. As we succeed in explaining more and more cognitive operations in

terms of patterns of electrical activity of specific neural circuits, it seems

we move ever farther from bridging the gap between the physical and the mental.

Indeed, each advance seems to further relegate mental activity to the status of

epiphenomenon – something that emerges from the physical activity of the brain

but that plays no part in controlling it. It seems difficult to reconcile the

reductionist, reverse-engineering approach to brain function with the idea that

we human beings have thoughts, desires, goals and beliefs that influence our

actions. If actions are driven by the physical flow of ions through networks of

neurons, then is there any room or even any need for psychological explanations

of behaviour?

How

vs Why

To me, that depends on what level of

explanation is being sought. If you want to understand how an organism behaves, it is perfectly possible to describe the

mechanisms by which it processes sensory inputs, infers a model of the outside

world, integrates that information with its current state, weights a variety of

options for actions based on past experience and predicted consequences,

inhibits all but one of those options, conveys commands to the motor system and

executes the action. If you fill in the details of each of those steps, that

might seem to be a complete explanation of the causal mechanisms of behaviour.

If, on the other hand, you want to know why it behaves a certain way, then an

explanation at the level of neural circuits (and ultimately at the level of

molecules, atoms and sub-atomic particles) is missing something. It’s missing

meaning and purpose. Those are not physical things but they can still have

causal power in physical systems.

Why

are why questions taboo?

Aristotle articulated a theory of

causality, which defined four causes or types of explanation for how natural

objects or systems (including living organisms) behave. The material cause deals with the physical identity of the components of a

system – what it is made of. On a more abstract level, the formal cause deals with

the form or organisation of those components. The efficient cause concerns

the forces outside the object that induce some change. And – finally – the final cause refers to the end or intended purpose of the thing. He saw

these as complementary and equally valid perspectives that can be taken to

provide explanations of natural phenomena.

Aristotle articulated a theory of

causality, which defined four causes or types of explanation for how natural

objects or systems (including living organisms) behave. The material cause deals with the physical identity of the components of a

system – what it is made of. On a more abstract level, the formal cause deals with

the form or organisation of those components. The efficient cause concerns

the forces outside the object that induce some change. And – finally – the final cause refers to the end or intended purpose of the thing. He saw

these as complementary and equally valid perspectives that can be taken to

provide explanations of natural phenomena.

However, Francis Bacon, the father of the

scientific method, argued that scientists should concern themselves only with

material and efficient causes in nature – also known as matter and motion.

Formal and final causes he consigned to Metaphysics, or what he called “magic”!

Those attitudes remain prevalent among scientists today, and for good reason – that

focus has ensured the phenomenal success of reductionist approaches that study

matter and motion and deduce mechanism.

Scientists are trained to be suspicious of “why

questions” – indeed, they are usually told explicitly that science cannot

answer such questions and shouldn’t try. And for most things in nature, that is

an apt admonition – really against anthropomorphising, or ascribing human

motives to inanimate objects, like single cells or molecules or even to organisms

with less complicated nervous systems and, presumably, less sophisticated inner

mental lives. Ironically, though, some people seem to think we shouldn’t even

anthropomorphise humans!

Causes of behaviour can be described both

at the level of mechanisms and at the level of reasons. There is no conflict

between those two levels of explanation nor is one privileged over the other –

both are active at the same time. Discussion of meaning does not imply some

mystical or supernatural force that over-rides physical causation. It’s not

that non-physical stuff pushes physical stuff around in some dualist dance. (After

all, “non-physical stuff” is a contradiction in terms). It’s that the

higher-order organisation of physical stuff – which has both informational

content and meaning for the organism

– constrains and directs how physical stuff moves, because it is directed towards a purpose.

Purpose is incorporated in artificial things

by design – the washing machine that is currently annoying me behaves the way

it does because it is designed to do so (though it could probably have been

designed to be quieter). I could explain how it works in purely physical terms

relating to the activity and interactions of all its components, but the reason

it behaves that way would be missing from such a description – the components

are arranged the way they are so that the machine can carry out its designed

function. In living things, purpose is not designed but is cumulatively

incorporated in hindsight by natural selection. The over-arching goals of

survival and reproduction, and the subsidiary goals of feeding, mating,

avoiding predators, nurturing young, etc., come pre-wired in the system through

millions of years of evolution.

Now, there’s a big difference between

saying higher-order design principles and evolutionary imperatives constrain the arrangements of neural

systems over long timeframes and claiming that top-down meaning directs the movements of molecules on a

moment-to-moment basis. Most bottom-up reductionists would admit the former but

challenge the latter. How can something abstract like meaning push molecules

around?

Determinism,

randomness and causal slack

The whole premise of neuroscientific

materialism is that all of the activities of the mind emerge from the actions

and interactions of the physical components of the brain – and nothing else. If you were transported, Star Trek-style, so that

all of your molecules and atoms were precisely recreated somewhere else, the

resultant being would be you – it

would have all the knowledge and memories, the personality traits and

psychological characteristics you have – in short, precisely duplicating your

brain down to the last physical detail, would duplicate your mind. All those

immaterial things that make your mind yours must be encoded in the physical arrangement of molecules in your brain right at this moment, as you read this.

The whole premise of neuroscientific

materialism is that all of the activities of the mind emerge from the actions

and interactions of the physical components of the brain – and nothing else. If you were transported, Star Trek-style, so that

all of your molecules and atoms were precisely recreated somewhere else, the

resultant being would be you – it

would have all the knowledge and memories, the personality traits and

psychological characteristics you have – in short, precisely duplicating your

brain down to the last physical detail, would duplicate your mind. All those

immaterial things that make your mind yours must be encoded in the physical arrangement of molecules in your brain right at this moment, as you read this.

To some (see examples below, in footnote), this implies a kind of neural determinism. The idea is that, given a

certain arrangement of atoms in your brain right at this second, the laws of

physics that control how such particles interact (the strong and weak nuclear

forces and the gravitational and electromagnetic forces), will lead, inevitably,

to a specific subsequent state of the brain. In this view, it doesn’t matter

what the arrangements of atoms mean,

the individual atoms will behave how they will behave regardless.

To me, this deterministic model of the

brain falls at the first hurdle, for one simple reason – we know that the

universe is not deterministic. If it were, then everything that happened since

the Big Bang and everything that will happen in the future would have been

predestined by the specific arrangements and states of all the molecules in the

universe at that moment. Thankfully, the universe doesn’t work that way – there

is substantial randomness at all levels, from quantum uncertainty to thermal

fluctuations to emergent noise in complex systems, such as living organisms. I

don’t mean just that things are so complex or chaotic that they are

unpredictable in practice – that is a statement about us, not about the world.

I am referring to the true randomness that demonstrably exists in the universe,

which makes nature essentially non-deterministic.

Now, if you are looking for something to

rescue free will from determinism, randomness by itself does not do the job –

after all, random “choices” are hardly freely willed. But that randomness, that

lack of determinacy, does introduce some room, some causal slack, for top-down

forces to causally influence the outcome. It means that the next lower-level

state of all of the components of your brain (which will entail your next

action) is not completely determined

merely by the individual states of all the molecular and atomic components of

your brain right at this second. There is therefore room for the higher-order arrangements

of the components to also have causal power, precisely because those arrangements

represent things (percepts, beliefs, goals) – they have meaning that is not

captured in lower-order descriptions.

Information

and Meaning

In information theory, a message (a string

or sequence of digits, letters, beeps, atoms, anything at all really) has a

quantifiable amount of information proportional to how unlikely that particular

arrangement is. So, there’s more information in knowing that a roll of a

six-sided die ended up a four than in knowing that a flip of a coin ended up

heads. That’s important for signal transmission especially because it

determines how compressible a message is and how efficiently it can be encoded

and transmitted, especially under imperfect or noisy conditions.

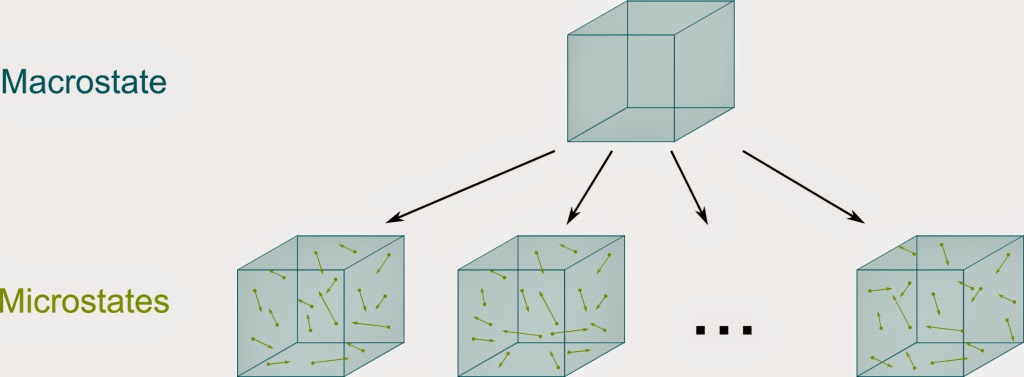

Interestingly, that measure is analogous to

the thermodynamic property of entropy, which can be thought of as an inverse

measure of how much order there is in a system. This reflects how likely it is

to be in the state that it’s in, relative to the total number of such states

that it could have been in (the coin

could only have been in two states, while the die could have been in six). In

physical terms, the entropy of a gas, for example, corresponds to how many

different organisations or microstates of its molecules would correspond to the

same macrostate, as characterised by specific temperature and pressure.

Actually, this analogy is not merely

metaphorical – it is literally true that information and entropy measure the

same thing. That is because information can’t just exist by itself in some

ethereal sense – it has to be instantiated in the physical arrangement of some

substrate. Landauer recognised that “any information that

has a physical representation must somehow be embedded in the statistical

mechanical degrees of freedom of a physical system”.

However, “entropy

only takes into account the probability of observing a specific event, so the

information it encapsulates is information about the underlying probability distribution, not the meaning of the events themselves.” In fact, the information

theory sense of information is not concerned at all with the semantic content

of the message. For sentences in a language or for mathematical expressions,

for example, information theory doesn’t care if the string is well-formed or

whether it is true or not.

So, the string: “your mother was a

hamster” has the same information content as its anagram “warmth or easy-to-use

harm”, but only the former has semantic content – i.e., it means something.

However, that meaning is not solely inherent in the string itself – it relies

on the receiver’s knowledge of the language and their resultant ability to

interpret what the individual words mean, what the phrase means and, further,

to be aware that it is intended as an insult. The string only means something

in the context of that knowledge.

In the nervous system, information is

physically carried in the arrangements of molecules at the cellular level and

in the patterns of electrical activity of neurons. For sensory information,

this pattern is imposed by physical objects or forces from the environment (e.g.,

photons, sound waves, odor molecules) impinging on sensory neurons and directly

inducing molecular changes and neuronal activity. The resultant patterns of

activity thus form a representation

of something in the world and therefore have information – order is enforced on

the system, driving one particular pattern of activity from an enormous

possible set of microstates. This is true not just for information about

sensory stimuli but also for representations of internal states, emotions,

goals, actions, etc. All of these are physically encoded in patterns of nerve

cell activity.

These patterns carry information in

different ways: in gradients of electrical potential in dendrites (an analog

signal), in the firing of action potentials (a digital signal), in the temporal

sequence of spikes from individual neurons (a temporally integrated signal), in

the spatial patterns of coincident firing across an ensemble (a spatially

integrated signal), and even in the trajectory of a network through state-space

over some period of time (a spatiotemporally integrated signal!). The

operations that carry out the spatial and temporal integration occur in the

process of transmitting the information from one set of neurons to another. It

is thus the higher-order patterns that encode information rather than the

lower-order details of the arrangements of all the molecules in the relevant

neurons at any given time-point.

But we’re not done yet. Just like that sentence about your mother (yeah, I went there), for that semantic content to mean anything to the organism it has to be interpreted, and that can only occur in the much broader context of everything the organism knows. (That’s why the French provocateur spoke in English to the stupid English knights, instead of saying “votre mère était un hamster”. Not much point insulting someone if they don’t know what it means).

The brain has two ways of representing information – one for transmission and one for storage. While information is transmitted in the flow of electrical activity in networks of neurons, as described above, it is stored at a biochemical and cellular level, through changes to the neural network, especially to the synaptic connections between neurons. Unlike a computer, the brain stores memory by changing its own hardware.

But we’re not done yet. Just like that sentence about your mother (yeah, I went there), for that semantic content to mean anything to the organism it has to be interpreted, and that can only occur in the much broader context of everything the organism knows. (That’s why the French provocateur spoke in English to the stupid English knights, instead of saying “votre mère était un hamster”. Not much point insulting someone if they don’t know what it means).

The brain has two ways of representing information – one for transmission and one for storage. While information is transmitted in the flow of electrical activity in networks of neurons, as described above, it is stored at a biochemical and cellular level, through changes to the neural network, especially to the synaptic connections between neurons. Unlike a computer, the brain stores memory by changing its own hardware.

Electrical signals are transformed into

chemical signals at synapses, where neurotransmitters are released by one

neuron and detected by another, in turn inducing a change in the electrical

activity of the receiving neuron. But synaptic transmission also induces

biochemical changes, which can act as a short-term or a long-term record of

activity. Those changes can alter the strength or dynamics of the synapse, so

that the next time the presynaptic neuron fires an electrical signal, the

output of the postsynaptic neuron will be different.

When such changes are implemented across a

network of neurons, they can make some patterns of activity easier to activate (or

reactivate) than others. This is thought to be the cellular basis of memory –

not just of overt, conscious memories, but also the implicit, subconscious

memories of all the patterns of activity that have happened in the brain.

Because these patterns comprise representations of external stimuli and

internal states, their history reflects the history of an organism’s

experience.

So, each of our brains has been literally

physically shaped by the events that have happened to us. That arrangement of

weighted synaptic connections constitutes the physical instantiation of our

past experience and accumulated knowledge and provides the context in which new

information is interpreted.

But I think there are still a couple

elements missing to really give significance to information. The first is

salience – some things are more important for the organism to pay attention to

at any given moment than others. The brain has systems to attribute salience to

various stimuli, based on things like novelty, relevance to a current goal

(food is more salient when you are hungry, for example), current threat

sensitivity and recent experience (e.g., a loud noise is less salient if it has

been preceded by several quieter ones).

The second is value – our brains assign

positive or negative value to things, in a way that reflects our goals and our

evolutionary imperatives. Painful things are bad; things that smell of bacteria

are bad; things that taste of bitter/likely poisonous compounds are bad; social

defeat is bad; missing Breaking Bad is bad. Food is good; unless you’re dieting

in which case not eating is good; an opportunity to mate is (very) good; a pay

raise is good; finally finishing a blogpost is good.

The value of these things is not intrinsic

to them – it is a response of the organism, which reflects both evolutionary

imperatives and current states and goals (i.e., purpose). This isn’t done by magic – salience and value are

attributed by neuromodulatory systems that help set the responsiveness of other

circuits to various types of stimuli. They effectively change the weights of

synaptic connections and reconfigure neuronal networks, but they do it on the

fly, like a sound engineer increasing or decreasing the volume through

different channels.

Top-down

control and the emergence of agency

The hierarchical, multi-level structure of

the brain is the essential characteristic that allows this meaning to emerge

and have causal power. Information from lower-level brain areas is successively

integrated by higher-level areas, which eventually propose possible actions based

on the expected value of the predicted outcomes. The whole point of this design

is that higher levels do not care about the minutiae at lower levels. In fact,

the connections between sets of neurons are often explicitly designed to act as

filters, actively excluding information outside of a specific spatial or

temporal frequency. Higher-level neurons extract symbolic, higher-order

information inherent in the patterned, dynamic activity of the lower level

(typically integrated over space and time) in a way that does not depend on the

state of every atom or the position of every molecule or even the activity of

every neuron at any given moment.

There may be infinite arrangements of all

those components at the lower level that mean the same thing (that represent

the same higher-order information) and that would give rise to the same

response in the higher-level group of neurons. Another way to think about this

is to assess causality in a counterfactual sense: instead of asking whether

state A necessarily leads to state B, we can ask: if state A had been

different, would state B still have arisen? If there are cases where that is

true, then the full explanation of why state A leads to state B does not inhere

solely in its lower-level properties. Note that this does not violate physical

laws or conflict with them at all – it simply adds another level of causation

that is required to explain why state

A led to state B. The answer to that question lies in what state A means to the

organism.

To reiterate, the meaning of any pattern of

neural activity is given not just by the information it carries but by the

implications of that information for the organism. Those implications arise

from the experiences of the individual, from the associations it has made, the

contingencies it has learned from and the values it has assigned to past or

predicted outcomes. This is what the brain is for – learning from past

experience and abstracting the most general possible principles in order to

assign value to predicted outcomes of various possible actions across the

widest possible range of new situations.

This is how true agency can emerge. The organism escapes from a passive, deterministic

stimulus-response mode and ceases to be an automaton. Instead, it becomes an

active and autonomous entity. It chooses

actions based on the meaning of the available information, for that organism, weighted by values based on its own experiences and its

own goals and motives. In short, it ceases to be pushed around, offering no

resistance to every causal force, and becomes a cause in its own right.

This is how true agency can emerge. The organism escapes from a passive, deterministic

stimulus-response mode and ceases to be an automaton. Instead, it becomes an

active and autonomous entity. It chooses

actions based on the meaning of the available information, for that organism, weighted by values based on its own experiences and its

own goals and motives. In short, it ceases to be pushed around, offering no

resistance to every causal force, and becomes a cause in its own right.

This kind of emergence doesn’t violate

physical law. The system is still built of atoms and molecules and cells and

circuits. And changes to those components will still affect how the system

works. But that’s not all the system is. Complex, hierarchical and recursive

systems that incorporate information and meaning and purpose produce

astonishing and still-mysterious (but non-magical) emergent properties, like

life, like consciousness, like will.

Just because it’s turtles all the way down,

doesn’t mean it’s turtles all the way up.

Footnote: Here are some examples of prominent scientists and others who support the idea of a deterministic universe and who infer that free will is therefore an illusion (except Dennett and other compatibilists):

Stephen Hawking: "…the molecular basis of biology shows that biological processes are governed by the laws of physics and chemistry and therefore are as determined as the orbits of the planets. Recent experiments in neuroscience support the view that it is our physical brain, following the known laws of science, that determines our actions and not some agency that exists outside those laws…so it seems that we are no more than biological machines and that free will is just an illusion (Hawking and Mlodinow, 2010, emphasis added)." Quoted in this excellent blogpost: http://www.sociology.org/when-youre-wrong-youre-right-stephen-hawkings-implausible-defense-of-determinism/

Patrick Haggard: "As a neuroscientist, you've got to be a determinist. There are physical laws, which the electrical and chemical events in the brain obey. Under identical circumstances, you couldn't have done otherwise; there's no 'I' which can say 'I want to do otherwise'. It's richness of the action that you do make, acting smart rather than acting dumb, which is free will."

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/science/8058541/Neuroscience-free-will-and-determinism-Im-just-a-machine.html

Sam Harris: "How can we be “free” as conscious agents if everything that we consciously intend is caused by events in our brain that we do not intend and of which we are entirely unaware?" http://www.samharris.org/free-will

Jerry Coyne: "Your decisions result from molecular-based electrical impulses and chemical substances transmitted from one brain cell to another. These molecules must obey the laws of physics, so the outputs of our brain—our "choices"—are dictated by those laws." http://chronicle.com/article/Jerry-A-Coyne/131165/

Daniel Dennett: Who concedes physical determinism is true but sees free will as compatible with that. This is a move that I have never fully understood the logic of or found at all convincing, yet apparently some form of compatibilism is a majority view among philosophers these days. http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/compatibilism/

Further reading:

Baumeister RF, Masicampo EJ, Vohs KD. (2011) Do conscious thoughts cause behavior? Annu Rev Psychol. 2011;62:331-61. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=21126180

Björn Brembs (2011) Towards a scientific concept of free will as a biological trait: spontaneous actions and decision-making in invertebrates. Proc Biol Sci. 2011 Mar 22;278(1707):930-9. http://rspb.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/278/1707/930.full

Bob Doyle (2010) Jamesian Free Will, the Two-Stage Model of William James. William James Studies 2010, Vol. 5, pp. 1-28. williamjamesstudies.org/5.1/doyle.pdf

Buschman TJ, Miller EK.(2014) Goal-direction and top-down control. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2014 Nov 5;369(1655). http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25267814

Damasio, Antonio (1994). Descartes' Error: Emotion, Reason, and the Human Brain, HarperCollins Publisher, New York.

George Ellis (2009) Top-Down Causation and the Human Brain. In Downward Causation and the Neurobiology of Free Will. Nancey Murphy, George F.R. Ellis, and Timothy O’Connor (Eds.) Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg www.thedivineconspiracy.org/Z5235Y.pdf

Friston K. (2010) The free-energy principle: a unified brain theory? Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010 Feb;11(2):127-38. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20068583

James Gleick (2011) The Information: A History, a Theory, a Flood http://www.amazon.com/The-Information-History-Theory-Flood/dp/1400096235

Paul Glimcher: Indeterminacy in brain and behavior. Annu Rev Psychol. 2005;56:25-56. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15709928

Douglas Hofstadter (1979) Gödel, Escher, Bach www.physixfan.com/wp-content/files/GEBen.pdf

Douglas Hofstadter (2007) I am a Strange Loop occupytampa.org/files/tristan/i.am.a.strange.loop.pdf

William James (1884) The Dilemma of Determinism. http://www.rci.rutgers.edu/~stich/104_Master_File/104_Readings/James/James_DILEMMA_OF_DETERMINISM.pdf

Roger Sperry (1965) Mind, brain and humanist values. In New Views of the Nature of Man. ed. J. R. Platt, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1965. http://www.informationphilosopher.com/solutions/scientists/sperry/Mind_Brain_and_Humanist_Values.html

Roger Sperry (1991) In defense of mentalism and emergent interaction. Journal of Mind and Behavior 12:221-245 (1991) http://people.uncw.edu/puente/sperry/sperrypapers/80s-90s/270-1991.pdf

As I understand Dennett's position from the book Freedom Evolves, whether or not there is physical determinancy, the space of possibility is so vast that there is effective freedom. The possibilities that represent life are vanishing in number, but in every one of them there is a pattern of relation that survived largely through its own agency. ("Vast" vs "vanishing" is a recurring device in the book.)

ReplyDeleteThis agency has remained central, if not definitional, as life evolved, eventually producing the brain, which serves to predict the results of the actions it guides. This is not paradoxical because the brain is organized in layers, where the higher layers make predictions that guide the lower layers, effectively modelling the environment for the purpose of survival. (I recommend Andy Clark's paper "Whatever Next?" and the extensive discussion that followed. In particular it makes Friston's work more accessible.)

From this perspective agency did not "emerge" - it has always been present and has been enhanced by evolution.

Thanks Rick - I have read Clark's paper, which I thought was excellent, as well as the extensive discussions following it. I had a section on predictive inference that didn't make the final cut here.

DeleteI kind of vaguely get what Dennett is angling at, but still don't find it completely convincing and actively disagree with some of it (such as where the definition of the word inevitable gets you). In any case, we don't need to accept determinism, as it's not true. So there's really no need to go to great lengths to show that free will is compatible with it.

Kevin, I have to hand it to you, you make a wonderful post, chock filled with very useful bits of description expounding on the function of the brain and the nature of thought and decision, but you have managed to slip in some outrageous fallacious reasoning in order to support your (impossible) vision of free will. I'm sorry, it still don't fly. I've tackled most of the crazy free will beliefs, and they generally fall into a few categories. Yours is fairly unique, but you do make one classic type of error that most people defending free will do.

ReplyDeleteReaders, my post here covers much of this:

No, You Don’t Have Free Will, and This is Why | JayMan's Blog

See also Greg Cochran:

The Road Not Taken | West Hunter

"Actually ... it is literally true that information and entropy measure the same thing. That is because information can’t just exist by itself in some ethereal sense – it has to be instantiated in the physical arrangement of some substrate."

Well done! Good explanation. Of course, this is perhaps even more true than you're giving it credit for, since, in principle, information could exist in a purely abstract sense, but that's through math. But, as Max Tegmark argues (and as I generally regard to be true), all things mathematical are physical as well.

"However, 'entropy only takes into account the probability of observing a specific event, so the information it encapsulates is information about the underlying probability distribution, not the meaning of the events themselves.'"

Ah ha! This is where you first run into trouble here. Allow me to highlight: what is meaning? "Meaning" is just an additional layer of information, one that exists at a higher "level" in the information hierarchy. The contents of a piece of music do not get lost because we represent it with sheet notation instead of the frequencies of the sound waves involved. It is understood that the sheet notation "encodes" these lower-level pieces of information, at least when we go to play it.

But you seem to capture that point in this piece, but yet you get these:

"In fact, the information theory sense of information is not concerned at all with the semantic content of the message. For sentences in a language or for mathematical expressions, for example, information theory doesn’t care if the string is well-formed or whether it is true or not."

Sure, but we do. Those too are important pieces of information you're ignoring in your oversimplication of the matter.

"The operations that carry out the spatial and temporal integration occur in the process of transmitting the information from one set of neurons to another. It is thus the higher-order patterns that encode information rather than the lower-order details of the arrangements of all the molecules in the relevant neurons at any given time-point."

Oh don't be so sure about that. Again, this is an oversimplication from our point of view, and allows you to weasel in the idea that structural levels below a certain resolution have no impact on the precise function of the neural structure in question. That we don't actually know, yet. (cont'd part 2)

(cont'd from part 1):

ReplyDelete"The whole point of this design is that higher levels do not care about the minutiae at lower levels."

You give a brilliant description of how the brain stores and retrieves information, but somehow manage to slip in this fine non-sequitur?

Allow me to give you an analogy: in a way, you're likening the function of the brain to a computer, where, purportedly, nothing matters but the actual 0s and 1s being stored and processed, not the medium they're stored on anything "below" that level (such as the atoms and molecules making up the storage device). But this can easily proven to be false this way: try playing the latest Mortal Kombat game on a computer with a SSD hard drive vs. on one with a traditional magnetic hard drive (a slow one) containing exactly the same data. The outcome you get might vary considerably.

OK, you might object that that depends on human input. Instead imagine comparing the difference between two resource-hogging highly dynamic visual simulation programs running on two computers that are otherwise identical except for the nature of the hard drive used (or even the speed of the RAM used).

The point is (even discounting quantum randomness) that you're ignoring a key thing: chaos theory. Very small differences in initial conditions can have dramatically different results. You're trying to set some artificial threshold of scale below which differences in conditions don't matter. Yet, as far as the brain is concerned, we don't have a good enough idea where that threshold might lie – if it exists at all.

"There may be infinite arrangements of all those components at the lower level that mean the same thing (that represent the same higher-order information) and that would give rise to the same response in the higher-level group of neurons."

Maybe. Probably, in fact. That hardly means that all such arrangements have no effect.

"another way to think about this is to assess causality in a counterfactual sense: instead of asking whether state A necessarily leads to state B, we can ask: if state A had been different, would state B still have arisen? If there are cases where that is true, then the full explanation of why state A leads to state B does not inhere solely in its lower-level properties."

Uh, no. Seriously? Sure, there may be many cases of multiple roads leading to the same place, but that doesn't mean that appearance of state B did not depend on the lower-level processes, any more than flooding of a low-lying area resulting from water that could have flowed there from one of several channels didn't depend on the forces of fluid dynamics. This is merely a fortuitous circumstance.

"This is how true agency can emerge. The organism escapes from a passive, deterministic stimulus-response mode and ceases to be an automaton. Instead, it becomes an active and autonomous entity. It chooses actions based on the meaning of the available information, for that organism, weighted by values based on its own experiences and its own goals and motives. In short, it ceases to be pushed around, offering no resistance to every causal force, and becomes a cause in its own right."

Yes. Agency is a thing. Few who talk seriously against the existence of free will denies this. But, as I said, agency ≠ free will. All that means is that the system (the human brain) is sophisticated, as you have wonderfully demonstrated here. But you can add as many levels of complexity to a system and that system will still be completely dependent on physical processes – processes that act from the lowest levels upward. (cont'd part 3)

(cont'd from part 2):

ReplyDeleteLet's go back to example of tides and planetary motion as given in one of your sources advocating "top-down causation." We can model the tidal effect or even the motion of the planets without having to compute the effect of each atom individually because the equations involve simplify in such a way that makes modelling (read: approximating to a sufficient degree) their behavior easier. The effects of gravity still completely depend on the sum of the effects of each individual subatomic particle.

Just the same way, this agency you describe is just that, all those "self-directed" actions merely emerge from the actions of the particles that comprise the individual. Sure, are the patterns complex? Yes. Do they act in a specific set of ways? Yes. Do the arrangement of these particles produce things we ascribe "meaning" to? Yes. But does it all depend on the low-level properties? Totally.

Great attempt to rescue free well, but as usual, there is no there there.

Jaymans, The fallacy of your argument is simple. You fail to make the case the physical determinacy makes any difference at all to the freedom of living beings. The space of will is vast and bodies make real choices, which is the free will that matters. Even if we lived in a clockwork universe, this would still be true. See Dennett, Freedom Evolves.

ReplyDeleteRick, do you believe that rocks and tornadoes are also conscious living beings with free will? why or why not? Can you point to particular experiments which have been or could be performed? Are you confident your neighbor is a conscious living being? Could you someday be convinced that a completely deterministic A.I. might someday inspire you to believe that they have experiences and make decisions? What could prove this issue to you one way or the other?

DeleteExcellent article! You should give the talks I'm invited to! :-)

ReplyDeleteI've had several long discussions with Patrick Haggard on this topic and I've told him his stance on determinism is overdoing it. Essentially, as far as I could tell from these discussions, he's not a determinist, but he uses determinism as a way to keep beating dualism. I've tried to emphasize that there aren't many dualists left and that falsely claiming that the universe is deterministic when most of his audience know that's wrong is not a good strategy towards getting heard. Not sure how effective that was. Either way, he just seems to be using it against dualism, that was my impression.

Björn Brembs

Thanks Björn! I think most determinists don't really believe it, which is good because it goes against our experience that we "could have done otherwise" in most decisions. To say that we couldn't is really an exceptional claim and really all they show is that they can't see how we could (which is very different from actually proving that we can't). For me, the common-sense prior that we do have free will is far too strong to be overturned without very strong evidence. Denying the existence of free will (or at least autonomous agency) makes it seem like there's nothing there to explain, when in fact how such agency emerges is the central mystery of neuroscience! (And maybe of life).

DeleteThis whole thing of determinists "knowing it is wrong" and "not believing it" begs for an experimental approach - beginning with experiments to show which elements of our physical worlds are conscious and which are not. Ok i'll cut to the chase - there is no such experiment possible. That means that we can either exclude the very idea of conscious agency from our empirical theorizing - or the touchy-feely alternative is to use scientific ideas to verify our inherently unprovable intuitions.

DeleteWell, obviously I disagree. I think it's more than a non-scientific intuition to say that we "could have done otherwise" in any situation. It is simply our experience. It would take a lot more evidence to prove to me that that doesn't exist. Some people claim neuroscience provides such evidence but really it only shows that some actions are not consciously chosen and can be affected by subconscious processes. Well, we knew that. That doesn't mean that we never make deliberative choices - we clearly do, all the time. That's not touchy-feely, it's just mysterious how we do it.

DeleteThis comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDeleteKevin, I like your post a great deal, much more than what the rest of this post may indicate...

ReplyDeleteI'm writing because I am unsure of what you mean in the pivotal part of your reasoning: "the next lower-level state of all of the components of your brain (which will entail your next action) is not completely determined merely by the individual states of all the molecular and atomic components of your brain right at this second. There is therefore room for the higher-order arrangements of the components to also have causal power".

I see different ways to interpret this part and I can agree only with one. I'll describe the interpretation I would agree with, and see if you think I've got it right.

You mention that the (hierarchical and dynamic) neural network topology introduces higher scale patterns of activity that correspond to our representation of concepts and to what we refer as mental states (such as being hungry). These patterns are never exactly repeated at the lower (molecular) level, so there is some (causal) slack to play with: the larger scale patterns do not rely on the exact behaviour of this or that (lower scale) particle/molecule/synapse.

Evolution has constrained the possible neural-network architectures (or: has heavily biased the probability distribution of all possible architectures) so to favour the patterns that work (in terms of genes survival) and by doing so has created a correspondence between neural network architecture, activity patterns and what we understand as innate purposes. These in turn allow us to assign salience and meaning to sensory stimuli. On the neural level, it is all perfectly matched by different scales of network architecture, so that certain activity patterns happen to coincide with mental states, purposes and so forth, and have causal power on the eventual behaviour because the larger structures can eventually influence the behaviour of their smaller parts (the top-down causality that you are looking for); for example a neuron will integrate thousands of synaptic inputs collected on the dentritic arborisation (a large-ish scale), to eventually "decide" whether to activate the output synapse or not (a smaller scale event).

Does this make sense to you?

Yes, that all makes sense to me - I'm not sure it says everything I'm trying to say but I think I agree with all of it

DeleteExcellent! I wasn't trying to summarise your whole argument, only the part that I wasn't sure of.

DeleteI'll proceed on the next point of uncertainty, but please don't feel compelled to produce a lengthy reply: I don't want to become a burden!

Having cleared the key point, a new thing now puzzles me, and that is your need to invoke "causal slack". If you prefer, I could say that I don't understand where you stand in regard to free will. This is because my own understanding of your argument would lead to the form of compatibilism that I do embrace (it's Dennett-like, but not exactly the same).

The key point is about different perspectives, not the Aristotelian ones, but the difference between subjective, first-person perspective (where purpose/will, meaning and salience are directly experienced) and the third-person, scientific perspective. From the latter point of view, assuming perfect determinism, time is just another variable: an all-knowing computer will be able to determine the state of any deterministic system at any time (knowing the exact starting conditions). This negates the free part of free will, or the libertarian interpretation of free will. However, I don't think that in your own account it negates simple-will, agency or sense of agency. I hope this point is uncontroversial.

The next bit is the one that Dennett tries to complete by introducing "competence", and I agree with him, but have a different preference on how to explain the general idea. If we move back to the first-person perspective, we know we can have a legitimate sense of agency, meaning that we do use our own resources (the higher order neural-network activity patterns that you describe) to decide what to do next. However, from this position, we don't have any way to manipulate time, we have to go with the flow, and as a result, to know what we'll decide, we can only engage our decision-making systems and see what happens. We are thus making a decision based on our own preferences and inclinations, and these happen to coincide with the network-patterns at the physical level (a sort of not-very-strong free will). Therefore, whether the systems we use to make decisions are fully deterministic or not is entirely irrelevant from this perspective.

From the third-person scientific point of view, free-will does not exist, but only because in this "view" time is an independent variable. We are examining an entirely different "space". By shifting from the first person time-tied perspective to the third person, time-independent one, we transfer one degree of freedom from the individual into the time domain. Unsurprisingly, as the two views refer to the same reality, the degrees of freedom remain the same.

The result is: from the first-person stance, free will exists in the sense that individual organisms do make decisions, based on their own, peculiar, unique and contingent conditions. Furthermore, these decisions are always somewhat unpredictable for all practical purposes.

From the third person point of view, the decisions may or may not be entirely predictable (in theory), but this distinction has no effect on how the world works from the subjective stance.

In your case, if you accept my position, you can avoid having to rely on true randomness and causal slack, and still end up with a world that can be described and predicted in scientific terms, while allowing the validity of our sense of agency (at the very least).

I hope the above does not look like an incoherent stream of gibberish...

Thanks Sergio. I am sorry but I don't follow the argument about time as a separate degree of freedom, depending on whether you take a first-person or third-person perspective. In any case, I see no need to rescue free will from a deterministic universe, if the universe is not indeed deterministic.

DeleteI don't see any way to rationalise a universe in which every molecular interaction is predestined, with one in which we "could have done otherwise". Just appealing to layers of complexity doesn't help - it makes behaviour unpredictable but not free. That is why I think we need causal slack in the system to give some room for events to be caused by the meaning of information (encoded in the physical arrangement of molecules), as opposed to just the molecules themselves.

Of course, if I actually knew how that all worked I'd be writing the most important book ever published, not my wee blog!

D'oh!

DeleteI guess it's time to retire my 'incoherent stream of gibberish' and stop harassing you, then. I've been experimenting with different ways to put in words what feels like a very strong intuition, but I've never found a truly convincing way (usually means that the intuition is wrong).

The "degrees of freedom" approach is just the last failure of a long list, not worth feeling sorry about it.

Thanks for indulging with my lucubrations, I do appreciate!

"This is how true agency can emerge. The organism escapes from a passive, deterministic stimulus-response mode and ceases to be an automaton."

ReplyDeleteA nice thing to believe, but really not shown here (and of course not showable). You basically have to believe in something supernatural occuring in the quantum world. You have to believe that there is a mind in there which moves matter. You have to believe in this supernatural dualism. It's worth pointing out that the quantum world thwarts efforts at complete determinism, but that doesn't deliver us any proof of "individual experiences" as either causes or effects.

For those who interpret the Alain Aspect experiment to show fundamental non-locality, the non-local-causality which they see present is just a reflection of that belief they had going in. In other words, if you see human choices as deterministic, then there is nothing magical about the "random choice" of which variables to measure, and both ends of the experiment can fit in some light cone and then you have superdeterminism. To interpret the result as something other than superdeterminism is therefore a form of circular thinking.

Similarly the argument provided here is circular in a similar way. If we take it as a given that consciousness and agency (different but related concepts) objectively "exist" then our interpretations of phenomena will be colored by that, even though neither of these things can be proven.

I have to say that the experts quoted here take it for granted that decisions occur and experiences exist *in the objective world*. I don't see *my* decisions take place in the objective world, and I don't see the next person's.

It also doesn't make sense to say that consciousness is an *illusion* - since the very word suggests an objective "realness" to subjective experience by definition. My consciousness is realer than the empirically testable world. My neighbor's consciousness simply is not a part of the empirically testable world.

I think you've identified the problem with a lot of the thinking about free will and agency - it is essentially dualist. What I mean is, the position you take here - that "you basically have to believe in something supernatural occuring in the quantum world. You have to believe that there is a mind in there which moves matter" is founded on dualist intuitions. Once you start off thinking of mind and matter as different types of stuff, you're lost - you'll never square that circle.

DeleteWhat I am trying to articulate in this post is that mind is really just the higher-order arrangements of bits of stuff and that, because those higher-order arrangements *mean something*, that they can have causal power over the system - that a full explanation of behaviour must encompass that meaning.

Kevin, you aren't really getting the nub here. If you and I were watching a volcano erupt, what would you think if I said: >>Once you start off thinking of the volcano's mind and it's matter as different types of stuff, you're lost - you'll never square that circle.

DeleteWhat I am trying to articulate in this post is that the volcano's mind is really just the higher-order arrangements of bits of stuff and that, because those higher-order lava arrangements *mean something*, that they can have causal power over the system - that a full explanation of behaviour must encompass that meaning.<< You are hand-waving right across from experiences and beliefs about your own and others' consciousness and agency into assertions that consciousness and agency are "observed" to "exist" the same way that molecules are.

If primary consciousness is a process of making a direct bayesian inference about the most efficient means of achieving an immediate goal within a closed system while mediating for a constant uncertainty variable then that could be seen as deterministic if you assume that a cybernetic calculation of an optimal probability in a closed system results in a set and predictable response.

ReplyDeleteIf extended consciousness is a process of modeling environmental factors and past experiences internally and making multiple bayesian inferences in an internal loop to determine the most efficient means of achieving goals in more than one possible future while mediating for an exponentially increasing level of uncertainty then is that also deterministic?

The difference is that extended consciousness is not only making predictions about possible futures but it is also learning from multiple past calculations. Primary consciousness is learning from the present feedback and applying it to near future bayesian predictions. Many experiments prove that we do not have agency in the present, we are unconsciously reacting to stimuli.

Extended consciousness is learning from present feedback on multiple past calculations and applying it to multiple future calculations. Does that increase in complexity begin to constitute agency or the illusion of it? Do we really choose a particular imagined future course or are we genetically predisposed to one course? Does consciousness give us agency in the form of a constructed self narrative that alters future bayesian inferences?

I just watched a squirrel bury a nut in my front yard. He or she (or the selected genetic propensity to bury nuts) was making a prediction, or calculating the probabilities, about a possible future. Is he making a choice or just following genetic propensities? Does imagining alternate futures give us any more agency than he has?

Robert - thanks for that. I think your general framing of the increasing complexity of the system that incorporates past experiences and future predictions is very helpful.

DeleteIt is possible that a probabilistic system based on Bayesian inference could actually be deterministic if all weights are tightly specified at the molecular level. But we know they are not. There is noise at every level - from the quantum level up - noise in gene expression, noise in neural circuits, noise in biochemical reactions. So, to my mind at least, the decision-making system cannot possibly be so deterministic. Moreover, there is strong evidence that randomness is actively utilised in decision-making as it has extremely strong adaptive value. E.g., see here: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=21159679

Finally, you say "Many experiments prove that we do not have agency in the present, we are unconsciously reacting to stimuli." I don't know of any such experiments that would justify such a sweeping conclusion. Certainly there are many that show we are influenced by subconscious factors and that many of our decisions can be biased by such factors (especially in experimental set-ups). But that does not mean that we never make a deliberative decision or are incapable of executing agency.

This comment has been removed by the author.

DeleteFor anyone skeptical of the idea that neuronal circuits really do extract higher-order patterns rather than being driven by lower-level molecular details, this paper provides dramatic example of how information is integrated over time and value attributed in decision-making circuits http://www.jneurosci.org/content/34/48/16046.abstract

ReplyDeleteThis may be a stupid question (I'm not a physicist):

DeleteDoes randomness at the quantum level affect what happens at the macro level. In other words, has quantum randomness got anything to do with me predicting what would happen were I to kick a football?

As I understand it, physicists can explain what happens on small scales and what happens on large scales, but they cannot yet reconcile the two. So something may be random on a small scale, and yet (possibly) deterministic on a large scale? I'm always sceptical when quantum mechanics are used to elucidate philosophical problems...

PS I love your post and your entire blog. I read only two blogs - yours and Dorothy Bishop's. Both are fantastic, in my opinion.

To use a hypothetical example, let's just say that we knew for certain that, on average, one electron from my foot falls away each hour (for whatever reason), but we don't know *which* electron will fall away at any particular hour (it's random). For predicting what would happen when I kick a football, would it make any difference *which* electron(s) I had lost or gained, if on average I have roughly the same number of them? How does activity on one level translate to activity on another lever?

DeleteMight the same apply to individual neurons and neural networks?

That's really a key question and I don't think it's known how quantum noise cascades to the macro level. (Physicists don't seem to agree on whether there is real noise/randomness at the quantum level, but the consensus seems to be there is, or the many worlds interpretation => effective randomness in whatever ongoing "world" is realised).

DeleteOne thing I'm wondering about myself is whether the noise at the lowest level has to propagate up for determinism to be false (I think so) or whether determinism would fail even if you only have emergent noise at higher levels which generates effectively chaotic behaviour. You might argue that chaotic means only unpredictable (but still deterministic), but if it's unpredictable to the next level up - at the level of abstraction that the next level cares about - then maybe that's enough.

This stuff'll do your head in!

Nice, but: "It chooses actions based on the meaning of the available information, for that organism, weighted by values based on its own experiences and its own goals and motives." Here the "It", "organism", "values", "experiences", "goals" and "motives" are each just a particular configuration of neurons. Ultimately you're saying that some ("higher") neurons get information from other neurons and then make high level "decisions" to direct activity. That doesn't accord with my definition or (possibly illusory) experience of free will.

ReplyDeleteFor me, there are two hard problems. The first is consciousness in the most narrow sense - what is the "I" which experiences (separate from everything with a clear physical basis - memory, identity, emotions, perceptions, thoughts, etc.). Next, if there is an "I" which experiences, can it exert free will?

I dip into these topics occasionally to see where the field has got to. I don't really see the science getting anywhere except full determinism, and maybe it never can. So I suppose that makes me a dualist.

Thanks David. Clearly this post does not touch the hard problem of consciousness or of subjective experience. I really just wanted to describe a framework that I think leaves room for extended causation beyond a bottom-up determinism - causation that includes meaning (in the context of purpose) as a prime mover or at least an essential part of a full explanation for human behaviour. (Not just for humans actually - for lots of organisms).

DeleteTo connect that idea of agency to the idea of conscious free will we need to explain a lot more - consciousness, the self, subjectivity. Science can't do that yet but I don't see any reason that it won't be able to in principle - it just seems we haven't grasped the full extent of emergence yet or developed a scientific framework to think about it or profitably investigate it. But our current impasse does not lead me to favour either determinism or dualism - both seem like cop-outs to me.

Hello Kevin and greetings from NL, nice post:

ReplyDeleteI have few question you may clear it up for me please:

1. from QM : The world is “probabilistically deterministic”; the exact course of events we perceive is random, but that occurs within a probability function that evolves deterministic way.

Is that the position you hold? and if not, why?

2.the genes and genetics factors/epigenetics , bottom-up decision making, are already an determined factor for our behavior, the way we think, the speed we reason etc...so to speak determined our behavior and we are slaves of their determinacy? as most determinist still think about it?

Thanks and waiting your reply

For my 1st question, a small append to make it clear: Is that the case all human behavioral traits are heritable and can be predicted (at least statistically) by behavioral genetics ?

ReplyDeleteChieftains used to open a hole in someone's skull to determine why they weren't behaving and responding to authoritative commands, which is the origin of psychiatry and neurosurgery.

ReplyDeleteToday, they use sound & micro-sound to tell you what words mean (and drug you if you still don't respond).

Very good article. To me, the next question is: where do the top-level values etc come from? If they are the inevitable or random product of a system of whatever kind, then free will evaporates. I wonder if human causation at that level is neither inevitable nor random. For example, your article has caused this comment. My comment is not random. But however much one examines your article, my comment is not inevitable either.

ReplyDelete