Gay genes? Yeah, but no, well kind of… but, so what?

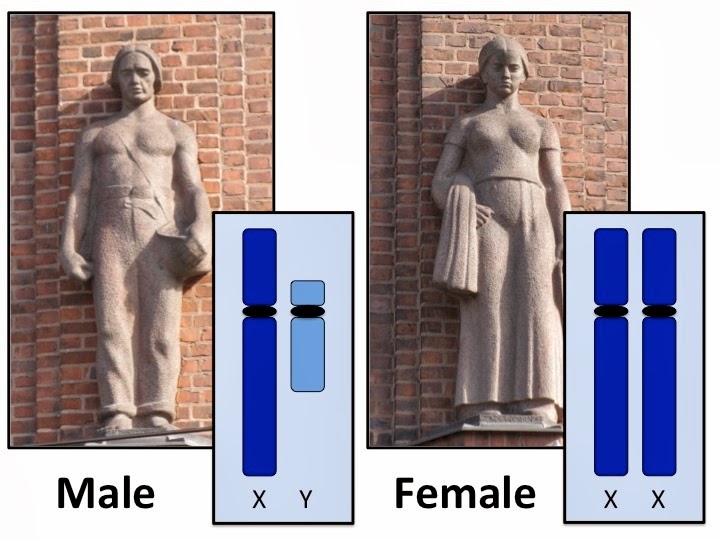

Sexual preference is one of the most

strongly genetically determined behavioural traits we know of. A single genetic

element is responsible for most of the variation in this trait across the

population. Nearly all (>95%) of the people who inherit this element are

sexually attracted to females, while about the same proportion of people who do

not inherit it are attracted to males. This attraction is innate, refractory to

change and affects behaviour in stereotyped ways, shaped and constrained by

cultural context. It is the commonest and strongest genetic effect on behaviour

that we know of in humans (in all mammals, actually). The genetic element is of

course the Y chromosome.

The idea that sexual behaviour can be

affected by – even largely determined by – our genes is therefore not only not

outlandish, it is trivially obvious. Yet claims that differences in sexual orientation may have at least a partly

genetic basis seem to provoke howls of scepticism and outrage from many, mostly

based not on scientific arguments but political ones.

The term sexual orientation refers to

whether your sexual preference matches the typical preference based on whether

or not you have a Y chromosome. It is important to realise that it therefore

refers to four different states, not two: (i) has Y chromosome, is attracted to

females; (ii) has Y chromosome, is attracted to males; (iii) does not have Y

chromosome, is attracted to males; (iv) does not have Y chromosome, is attracted

to females. We call two of these states heterosexual and two of them

homosexual. (This ignores the many individuals whose sexual

preferences are not so exclusive or rigid).

A recent twin study confirms that sexual

orientation is moderately heritable – that is, that variation in genes

contributes to variation in this trait. These effects are detected by looking

at pairs of twins and determining how often, when one of them is homosexual,

the other one is too. This rate is much higher (30-50%) in monozygotic, or

identical, twins (who share all of their DNA sequence), than in dizygotic, or

fraternal, twins (who share only half of their DNA), where the rate is 10-20%.

If we assume that the environments of pairs of mono- or dizygotic twins are

equally similar, then we can infer that the increased similarity in sexual

orientation in pairs of monozygotic twins is due to their increased genetic

similarity.

These data are not yet published (or peer

reviewed) but were presented by Dr. Michael Bailey at the recent American

Association for the Advancement of Science meeting (Feb 12th 2014) and widely reported on.

They confirm and extend findings from multiple previous twin studies across

several different countries, which have all found fairly similar results (see here for more details). Overall, the conclusion that sexual orientation is

partly heritable was already firmly made.

The reaction to news of this recent study reveals

a deep disquiet with the idea that homosexuality may arise due to genetic

differences. First, there are those who scoff at the idea that such a complex

behaviour could be determined by what may be only a small number of genetic

differences – perhaps only one. As I recently discussed, this view is based on

a fundamental misunderstanding of what genetic findings really mean. Finding

that a trait (a difference in some

system) can be affected by a single genetic difference does not mean a single

gene is responsible for crafting the entire system – it simply means that the

system does not work normally in the absence of that gene. (Just as a car does

not work well without its steering wheel).

Others have expressed a variety of personal

and political reactions to these findings, ranging from welcoming further

evidence of a biological basis for sexual orientation to worry that it will be

used to label homosexuality a genetic disorder and even to enable selective

abortion based on genetic prediction. The latter possibility may be made more

technically feasible by the other aspect of the recently reported study, which

was the claim that they have mapped genetic variants affecting sexual

orientation to two specific regions of the genome. (This doesn’t mean they have

identified specific genetic variants but may be a step towards doing so).

Let’s explore what the data in this case

really show and really mean. A variety of conclusions can be drawn from this

and previous studies:

1.

Differences in sexual

orientation are partly attributable to genetic differences.

2.

Sexual orientation in males and

females is controlled by distinct sets of genes. (Dizygotic twins of opposite

sex show no increased similarity in sexual orientation compared to unrelated

people – if a female twin is gay, there is no increased likelihood that her

twin brother will be too, and vice versa).

3.

Male sexual orientation is

rather more strongly heritable than female.

4.

The shared family environment

has no effect on male sexual orientation but may have a small effect on female

sexual orientation.

5.

There must also be non-genetic

factors influencing this trait, as monozygotic twins are still often discordant

(more often than concordant, in fact).

The fact that sexual orientation in males

and females is influenced by distinct sets of genetic variants is interesting

and leads to a fundamental insight: heterosexuality is not a single default

state. It emerges from distinct biological processes that actively match the

brain circuitry of (i) males or (ii) females to their chromosomal and gonadal sex so that most individuals who carry a Y chromosome are attracted to females

and most people who do not are attracted to males.

What is being regulated, biologically, is

not sexual orientation (whether you are attracted to people of the same or

opposite sex), but sexual preference (whether you are attracted to males or

females). Given how complex the processes of sexual differentiation of the brain are (involving the actions of many different genes), it is not surprising

that they can sometimes be impaired due to variation in those genes, leading to

a failure to match sexual preference to chromosomal sex. Indeed, we know of

many specific mutations that can lead to exactly such effects in other mammals

– it would be surprising if similar events did not occur in humans.

What is being regulated, biologically, is

not sexual orientation (whether you are attracted to people of the same or

opposite sex), but sexual preference (whether you are attracted to males or

females). Given how complex the processes of sexual differentiation of the brain are (involving the actions of many different genes), it is not surprising

that they can sometimes be impaired due to variation in those genes, leading to

a failure to match sexual preference to chromosomal sex. Indeed, we know of

many specific mutations that can lead to exactly such effects in other mammals

– it would be surprising if similar events did not occur in humans.

These studies are consistent with the idea

that sexual preference is a biological trait – an innate characteristic of an

individual, not strongly affected by experience or family upbringing. Not a

choice, in other words. We didn’t need genetics to tell us that – personal

experience does just fine for most people. But this kind of evidence becomes

important when some places in the world (like Uganda, recently) appeal to

science to claim (wrongly) that there is evidence that homosexuality is an

active choice and use that claim directly to justify criminalisation of

homosexual behaviour.

Importantly, the fact that sexual

orientation is only partly heritable

does not at all undermine the conclusion that it is a completely biological

trait. Just because monozygotic twins are not always concordant for sexual

orientation does not mean the trait is not completely innate. Typically,

geneticists use the term “non-shared environmental variance” to refer to

factors that influence a trait outside of shared genes or shared family

environment. The non-shared environment term encompasses those effects that

explain why monozygotic twins are actually less than identical for many traits

(reflecting additional factors that contribute to variance in the trait across

the population generally).

The terminology is rather unfortunate

because “environmental” does not have its normal colloquial meaning in this

context. It does not necessarily mean that some experience that an individual

has influences their phenotype. Firstly, it encompasses measurement error (just

the difficulty in accurately measuring the trait, which is particularly

important for behavioural traits). Secondly, it includes environmental effects

prior to birth (in utero), which may be especially important for brain

development. And finally, it also includes chance or noise – in this case,

intrinsic developmental variation that can have dramatic effects on the end-state

or outcome of brain development. This process is incredibly complex and noisy,

in engineering terms, and the outcome is, like baking a cake, never the same

twice. By the time they are born (when the buns come out of the oven), the

brains of monozygotic twins are already highly unique.

The terminology is rather unfortunate

because “environmental” does not have its normal colloquial meaning in this

context. It does not necessarily mean that some experience that an individual

has influences their phenotype. Firstly, it encompasses measurement error (just

the difficulty in accurately measuring the trait, which is particularly

important for behavioural traits). Secondly, it includes environmental effects

prior to birth (in utero), which may be especially important for brain

development. And finally, it also includes chance or noise – in this case,

intrinsic developmental variation that can have dramatic effects on the end-state

or outcome of brain development. This process is incredibly complex and noisy,

in engineering terms, and the outcome is, like baking a cake, never the same

twice. By the time they are born (when the buns come out of the oven), the

brains of monozygotic twins are already highly unique.

Genetic differences may thus change the probability of an outcome over many

instances, without determining the

specific outcome in any individual.

A useful analogy is to handedness.

Handedness is only moderately heritable but is effectively completely innate or

intrinsic to the individual. This is true even though the preference for using

one hand over the other emerges only over time. The harsh experiences of many

in the past who were forced (sometimes with deeply cruel and painful methods)

to write with their right hands because left-handedness was seen as aberrant –

even sinful – attest to the fact that the innate preference cannot readily be

overridden. All the evidence suggests this is also the case for sexual

preference.

What about concerns that these findings

could be used as justification for labelling homosexuality a disorder? These

are probably somewhat justified – no doubt some people will use it like that. And

that places a responsibility on geneticists to explain that just because

something is caused by genetic variants – i.e., mutations – does not mean it

necessarily should be considered a disorder. We don’t consider red hair a

disorder, or blue eyes, or pale skin, or – any longer – left-handedness. All of

those are caused by mutations.

The word mutation is rather loaded, but in

truth we are all mutants. Each of us carries hundreds of thousands of genetic

variants, and hundreds of those are rare, serious mutations that affect the

function of some protein. Many of those cause some kind of difference to our

phenotype (the outward expression of our genotype). But a difference is only

considered a disorder if it negatively impacts on someone’s life. And

homosexuality is only a disorder if society makes it one.

Concordance for homosexuality (males) in monozygotic twins is lower than 30-50%: more like 25%, from twin registry studies.

ReplyDeleteFrom a Darwinian view, homosexuality is a disorder whether anyone says it is or not. It greatly reduces reproductive fitness, big surprise.

Concordance rates vary across studies - latest (and largest) one apparently ~40%. Exact number not that important - what is important is excess over rate in dizygotic twins.

DeleteJust because something reduces Darwinian fitness does not make it a disorder - those are based on completely different criteria. We do not diagnose or categorise people on evolutionary grounds.

Can you tell me the source for that 40% twin study? I wasn't aware of it.

DeleteThat figure is from reports of latest study (not yet published). See here for links to other large twin studies: http://www.wiringthebrain.com/2014/03/gay-genes-yeah-but-no-well-kind-of-but.html?showComment=1395734941794#c3768417674897587425 . The concordance rates and heritability estimates vary across a pretty wide range.

DeleteDoes the Y chromosome really explain that much variance? I don't think that it is that simple. Consider, for example, people with androgen insensitivity syndrome: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1429/

ReplyDeleteTo me, androgen insensitivity and related conditions are the exceptions that prove the rule.

DeleteKevin is correct. It is not juts the Y chromosome, but more specifically the SRY gene with the Testes Determining Factor (TDF). Androgen insensitivity among several other disorders are a failure of the mechanism for TDF to either properly function or act on its receptors. They are exceptions that prove the given function.

Delete"Just because something reduces Darwinian fitness does not make it a disorder - those are based on completely different criteria. We do not diagnose or categorise people on evolutionary grounds."

ReplyDeleteWell, that's certainly an odd statement.

Would you say that a female who has polycystic ovaries or endo- metriosis resulting in blocked fallopian tubes doesn't suffer from any disorder? The conditions greatly reduce or prevent her ability to conceive.

Would you say a man with low sperm production or with impaired sperm motility, either making it unlikely he will be able to impregnate a mate, has a disorder?

You would answer "yes" to both the above scenarios, I am sure.

A man who has healthy sperm along with a functioning sperm delivery system yet who aims that sperm at an infertile target has a disorder no different from the polycystic woman or the healthy sperm-challenged male. The only difference is locale of the disorder. This time it's the brain.

Something is called a disorder, in clinical terms, if people suffer from it. Evolutionary fitness doesn't come into that definition. There are tons of traits that lower fitness that we don't consider disorders - like shyness, or recklessness, for example.

Delete"Something is called a disorder, in clinical terms, if people suffer from it. "

DeleteReally? " Suffer from it" as in physically or emotionally or both?

Odd comment ...again, esp. from one trained as a scientist.

How about a person who is blind in one eye, like my aunt? She had some kind of an eye infection as a child and was lucky to retain vision in one eye. She learned to adjust to daily life with one good eye. However, a "condition" is responsible for blindness in one eye.

What of my father? High cholesterol and triglycerides? So far, no suffering at all. Nevertheless, modern medicine considers he has a condition that could kill him prematurely. It's a condition.

Myopia? I don't actually "suffer" from it aside from its being a pain to have to search for my glasses or bother to put in contact lenses, but were they lost to me, I'd not be safe nor would anyone else on the road. If I had to track and kill prey, my distance vision would severely hinder my success and I'd starve. It's a condition.

As for "shyness" or "recklessness" of the garden variety, are you sure these characteristics lower reproduction?

On the other hand, those on the extreme of the autism spectrum do indeed have some sort of condition preventing their socialization and thus their reproductive odds.

You're playing word games out of some sense of righteousness, I would imagine.

"You're playing word games out of some sense of righteousness, I would imagine."

DeletePot kettle black.

"A man who has healthy sperm along with a functioning sperm delivery system yet who aims that sperm at an infertile target has a disorder no different from the polycystic woman or the healthy sperm-challenged male. The only difference is locale of the disorder. This time it's the brain."

DeleteBy your definition Ted, my husband has a brain disorder too. I'm infertile, so every time he aims his perfectly functioning junk my way it's destined for evolutionary failure. Also, so is every man who aims at post-menopausal women.

I doubt that homosexuality is innate (and I also doubt that handedness is). Babies are not born with sexual preference. It is more likely that homosexuality is developmental. Waddington's epigenetic landscape explains why it is so difficult to change a trait after it occurred. An example may be mental retardation in the deaf (that was considered innate in the past), it is prevented if communication (e.g. sign language) begins early, but if communication is delayed until after a critical period MR occur and is very difficult to reverse.

ReplyDeleteThanks for your comment Guy. Actually, I agree - innate is not the best word, but it's hard to find a better one that captures the meaning. Clearly, sexual preference does not emerge until sexual interest emerges. And hand preference is also apparently fluid for a while before it becomes fixed - that does not mean it can be changed by intervening at an early stage, however. We may be witnessing a trajectory that is fairly fixed and already intrinsic to the individual, even though they have not yet reached the endpoint. Alternatively, it may be more fluid but based on internal processes, which are not sensitive to outside forces. Or, for some traits, experience may really be crucial during some critical period - I don't think there's any evidence that that is the case for either sexual preference or handedness.

DeleteHmm.....can't really say much about sexuality, but handedness? Well according to my family, I naturally tended left until I broke my arm as a toddler. I was then taught to be right handed. I honestly don't feel like I've ever been any other way but right handed. If what I'm told is true, it does seem to suggest something about experiential tweaking of a trait. Just a thought

ReplyDeleteWhy Bisexuality is ignored or is treated as a variant of homosexuality? essentialist researchers present as fact (as universal, ahistorical and acultural) a model of sexuality that is one among many possible models of sexuality, and that is particular to contemporary western culture.

ReplyDeleteThe only alternative to including bisexuals in the homosexual group is to abandon a dichotomous model of homosexuality and (possibly) the concept of ‘sexual orientation’, and to acknowledge that sexuality is more fluid and messy than the dichotomous model suggests.

Some men identify firmly as heterosexual but have regular

sex with other men (e.g., men in prison or in the armed forces and other men who might be labelled ‘situational homosexuals’ or men who have sex with men (MSM)). Some people identify with a particular sexual identity because of political or ideological reasons (e.g., political lesbians). Some people identify as bisexual but are in a long-term monogamous relationship with someone of a different sex. Some people feel that their engagement in particular sexual communities or practices is a more important indicator of their sexuality than the sex/gender of the people they have sex with (e.g.,somepeople who engagein BDSM). These are just a few examples of the complexities in how people identify their sexuality and experience and express their sexual desires. If these people were invited to participate in a biological study, how would they be classified? Which aspect of sexuality – how we label and identify our sexuality (now or in the past), how we behave (now or in the past), what we desire (now or in the past) – counts as ‘the truth’ of our sexuality? Typically, essentialist researchers ignore the meanings people give to their sexualities and attempt to classify them in terms of the dichotomous heterosexual/homosexual model.