Sex on the brain – a tale of two studies

The issue of whether there are biological

differences between male and female brains is a fraught one and an area where

political positions or prior expectations seem to have a strong influence on

the interpretation of scientific data. These trends are illustrated by two

papers published in the last couple years, which, despite fairly comparable

findings, were interpreted in almost polar opposite fashions.

Both studies found strong group differences

between male and female brains, one in volume of brain areas, the other in

structural connectivity. But the authors of one study went on to

(over)interpret these group differences as the basis for sex differences in

cognition, while the other downplayed them entirely and instead emphasised the

inherent variability within genders to conclude that there was no such thing as

a “male brain” or a “female brain”. Both

received extensive coverage in the media, fuelled by the associated press

releases, resulting in headlines making hilariously contradictory claims, even

in the same newspaper!

The 2013 study was described with these headlines:

Brain Connectivity Study Reveals Striking Differences Between Men and Women

Male and female brains wired differently, scans reveal (The Guardian)

The 2015 study with these:

The brains of men and women aren’t really that different, study finds

Men are from Mars, women are from Venus? New brain study says not (The Guardian again!)

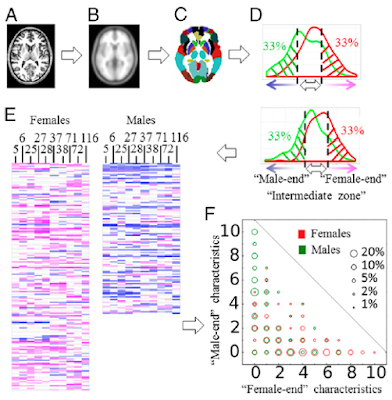

Let’s look at the more recent one first, to

see what the data actually show and how they were analysed and interpreted. Daphna

Joel and colleagues analysed MRI scans of 169 females and 112 males, and

segmented them into 116 regions using a standard brain atlas. By analysing how

much warping was required to map each brain onto a reference template, it was

possible to compare the relative grey matter volume of all these regions across

the two sexes. From this group comparison the 10 regions showing the largest

sex differences were chosen for subsequent analyses.

So far, so good: the primary finding is

that there are statistically significant group

differences between males and females in grey matter volume across many

brain regions. That’s nothing new – a recent meta-analysis of 167 studies

confirms consistent group sex differences in many brain areas between men and

women

The authors went on, however, to ask what

could have been a more interesting question: across those 10 regions, how “male”

or “female” were the structures of individual brains? This is where the

subjectivity comes in – there are many ways to analyse these data and the

authors chose arguably the most simplistic and extreme one, which enabled them

to draw the conclusion that male and female brains are not categorically

different.

They report that: “35%

percent of brains showed substantial variability, and only 6% of brains were

internally consistent”. Importantly they chose to classify only those

subjects showing extreme male or female values for all 10 regions as

“internally consistent”. A quick look at panel E of the figure below shows that

while such brains may indeed be rare, most of the female brains showed a mostly

female pattern (lots of pink) while most of the male brains showed a mostly

male pattern (lots of blue – don’t blame me, I didn’t pick the colours!).

There is, in fact, nothing at all

surprising in their finding of substantial variability within individuals. To

explain why, consider the distributions for height for males and females.

These distributions are very wide and mostly overlapping but there is a strong

and consistent group difference in the mean – the distribution for males is

shifted to the right. For any individual, however, knowing their sex gives

almost no predictive power for how tall they are. What the group difference

does suggest is the following: if I know how tall a particular woman is, I can

say that if she had been a man (but was genetically otherwise identical) she

would probably have been a little taller than that. She may happen to fall at

the low or high end of the overall spectrum for

other reasons, but that prediction remains the same. The existence of the

group difference does not suggest that all males should be at the extreme “male”

end of the height distribution or they’re not really very manly at all. That

would be true if all other things were

equal, but they’re not equal, and those other variations, which have

nothing to do with sex, have a much bigger effect on final height than the sex

effect does.

Now, consider what will happen if we have

ten different variables, each showing that same sort of wide distribution with

an even smaller group sex effect. If the volumes of different brain regions

vary independently within individuals (taking overall brain volume out of the

equation - as shown here, for example),

then we should expect some of these values to fall more towards the male end

and others more towards the female end in any individual simply due to that

underlying variation, which has nothing to do with sex. It would be extremely

unlikely to end up at the extreme end for all ten regions, by chance, and such

individuals should thus be extremely rare, as observed.

So, the fact that each individual shows

this kind of pattern does not mean that each of us has a “mosaic brain” that is

partly male and partly female, as claimed by the authors. It is simply exactly

what is expected given that sex is only one of the factors affecting the size

of each of these regions. We can’t know for each individual what the size of

each region would have been if their

sex were different (which is really what we’d like to know) – we can only

deduce from the group average effects that there would likely have been some

effect.

The headlines suggesting that male and

female brains are not that different are thus not well supported by these

findings at all. The group differences are clear and highly significant. And

even if very few of the males or females are at the extreme end of the

distribution for all ten of these

regions, the overall pattern suggests that you could build a very good

classifier from the volumes of these ten regions taken together, which would be

quite successful at predicting whether a given brain scan came from a male or a

female. Indeed, this would have been a far more objective test of whether MRI

volumetric differences between male and female brains are categorical or

dimensional.

Given this, it is interesting to ask why

the authors chose to analyse and present their data in the way they did. This

is what they say in the introduction to the paper:

"Documented sex/gender* differences in the brain are

often taken as support of a sexually dimorphic view of human brains (“female

brain” vs. “male brain”), and consequently, of a sexually

dimorphic view of human behavior, cognition, personality, attitudes, and other

gender characteristics (3). Joel (4, 5) has recently argued that the existence

of sex/gender differences in the brain is not sufficient to conclude that human

brains belong to two distinct categories. Rather, such a distinction requires the

fulfillment of two conditions: one, the form of the elements that show

sex/gender differences should be dimorphic, that is, with little overlap

between the forms of the elements in males and females. Two, there should be a

high degree of internal consistency in the form of the different elements of a

single brain (e.g., all elements have the “male” form)."

It seems pretty clear from that that the

authors set out to show that male and female brains are not that different, or

at least not dimorphic. In particular, they take aim at a paper by Madura Ingalhalikar and colleagues (their reference 3, above), which is the second

paper I wish to discuss. These authors found comparable group difference results

as Joel et al (using a different measure of brain structure), yet reached

almost opposite conclusions.

They used diffusion tensor imaging

to define the structural connectivity networks across the brains of 949 youths

(428 males and 521 females). They then analysed these networks using a variety

of statistical measures of regional and global connectivity and compared these

between males and females. They found that females had greater connectivity

between hemispheres than males, on average, while males had greater

connectivity within each hemisphere. Males also showed greater local

connectivity and concomitantly increased modularity in the network (again, on

average).

(In this figure from the paper, the top panel shows connections that are stronger in males, the bottom those that are stronger in females; blue are intrahemispheric, orange are interhemispheric).

Once again, so far, so good – the results

look significant and interesting. (It would have been nice to see the analyses

done with a discovery and replication sample, instead of one big group but at

least it is a large sample). Where these authors got onto shakier ground was in

extrapolating their findings as explanations for a variety of group differences

in cognition between men and women. The participants in the structural

connectivity analysis were part of a larger sample for which cognitive data had

already been obtained, showing sex differences in a variety of domains. Such differences have been widely documented and range from quite small to

fairly large (see here for a meta-analysis).

However, the idea that the structural

connectivity network differences observed are the cause of such cognitive differences is entirely speculative. I

have nothing against speculation, per se, and the discussion section of a paper

is a perfect place to explore the possible implications of one’s results. Where

this got a bit out of hand was in the associated press release and the

consequent media coverage. This is from the press release itself:

For instance, on average, men are more likely better at learning and performing a single task at hand, like cycling or navigating directions, whereas women have superior memory and social cognition skills, making them more equipped for multitasking and creating solutions that work for a group. They have a mentalistic approach, so to speak. "

Those kinds of assertive generalisations,

and especially the idea that the connectivity findings provide a neural basis

for them, are not at all supported by the data and rightly provoked howls of

protest from the scientific community. This included commentary by Joel and colleagues , to which Ingalhalikar and colleagues responded.

The unfortunate outcome was that the authors’ over-extrapolation ended up

undermining trust in their primary findings, which actually look quite solid in

themselves.

To my mind, both these studies over-reached

in the interpretation of their results, ironically drawing opposite conclusions

from what are broadly comparable primary findings. More generally, it also

seems that a little more humility is in order in drawing sweeping conclusions

from these kinds of studies, given the crudeness of group-wise volumetric and

tractography analyses and the very low resolution of MRI scans. Even if such

scans showed no consistent group differences between male and female brains,

this would not imply that male and female brains are not different. It would

only imply such differences could not be detected by MRI. We know there are

many differences in the numbers of neurons in small brain regions or numbers of

connections between regions in male and female brains that are invisible to

MRI, not to mention sex differences in densities of synaptic spines or other

subcellular parameters that have also been demonstrated (as in this recent example).

A final note: why should we care? Why

should we investigate sex differences in the brain? And if we find them, what

are their implications for public policies? Many people are rightly concerned

that demonstrations of biological differences in brain structure between males

and females will be used to reinforce the idea of systematic differences in

cognitive abilities and justify sexism. Of course, even if such differences were

large and consistent across individuals, it would not imply one version is

better than the other. But more importantly, the distributions for cognitive

domains are so overlapping and the sex effects typically so small that

inferring anything about the cognitive profiles of individuals on the basis of

these group differences is, simply put, a very bad bet. Sex differences for

interests are a little bit bigger, but still by no means categorical and there is likely a strong cultural

reinforcement of gender norms in this area.

There are, however, other areas where there

are more robust sex differences. The most obvious but also the most commonly

over-looked of these is sexual preference – something in the brains of males

makes the vast majority of them sexually attracted to females, and vice versa.

This is by far the strongest genetic effect on behaviour that we know of in

humans (mediated by the SRY gene on the Y chromosome). It would therefore be

interesting to find out how that preference is wired into the brain, as an

exemplar for how genes can influence innate behaviour. Sex differences in physical

aggression are also large and another important topic to understand (as are differences in idiotic behaviour as measured by the Darwin awards!).

Finally, though, a main reason we should

care is due to the large sex differences in prevalence of psychiatric conditions, which range from autism, ADHD and Tourette syndrome (much more common

in males), to schizophrenia and dyslexia (more common in males), to depression

(more common in females) and eating disorders (much more common in females).

There is strong and consistent evidence, for example, that females are somewhat protected against the effects of mutations that typically cause autism in males. Females may carry such mutations with relatively little clinical effect;

conversely, females who do have autistic symptoms tend to have larger or more

severe mutations than affected males (suggesting that it takes a more drastic

insult at the genetic level to push a female brain into a clinically autistic

state). Understanding how sex influences vulnerability to these conditions is thus

a hugely important question.

Too important to let politics, bias or spin

affect our interpretation of scientific findings.

I know this isn't the purpose of the article, but one minor correction:

ReplyDeleteKnowing the trends of height does have predictive power. If you select an individual at random, I would be correct in more instances if I guessed the height to be the mean height of that gender. I would have a probabilistic predictive ability equal to the height of the normal curve at the point of the mean.

Furthermore, if we change the game slightly to where it is better to come closer to the truth, I have extended my predictive capability. By guessing the mean of the gender I would again be more correct more often than guessing based on, for example, the average height of human beings as a whole.

The brain is of course a lot more complex, so it isn't necessarily the case that you are closer to any mean, and also our perspective of stereotypes, for example, are poorer guiding tools because they use extreme values of feminity or masculinity rather than the mean. However, even in these cases the argument could and should be made that guessing an extreme is closer to the truth, even thiugh still strictly false.

Thanks Andreas - you're completely right, but still talking in a probabilistic sense. Knowing the sex of a person gives you very little power to accurately predict their actual height. You can guess the mean of that gender and you'd be right there more frequently than anywhere else, but still wrong VASTLY more frequently than you're right. (In other words, the underlying variability is much greater than the size of the sex difference).

DeleteFor me, what would be interesting is whether these group differences arise early during ontogenesis or whether they emerge gradually over developmental time.

ReplyDeleteFor example, I read somewhere that (on average) mothers talk more to baby girls than baby boys. Boys and girls are treated differently from a very early age. So some between-group brain differences are unsurprising. What interests me is *how* these differences emerge. A very difficult study to carry out!

Baron Cohen reports an experiment comparing the interest shown by 24 hour old babies in (a) faces and (b) mechanical mobiles which appears to be consistent with the females preferring (a) and the males preferring (b). But as he says, that still leaves 24 hours for cultural pressures to do their work.

DeleteI don't believe even the most ardent enthusiast for the importance of genes denies that it is testosterone that masculines the brain, not the SRY gene operating directly. So no one doubts that it takes a bit of time for the genes to work their indirect effect during the course of development. And then testosterone has another go during puberty. So even if you discounted all environmental influences, the difference must emerge over developmental time.